What Is Rapport? Learn About The Best Techniques To Generate A Good Relationship

The word rapport comes from the French rapporter and literally means to bring something to change. If we focus it on communication between two people, it refers to what one person sends to another, the latter returns it. In simpler words, rapport refers to the bond between two or more human beings, to the psychological and emotional harmony that is needed so that changes can take place in any of the parts.

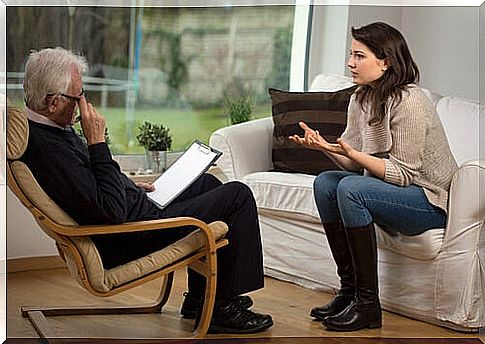

The school, the prior psychological evaluation or the techniques implemented in the course of treatment are extremely important in order to cure the patient. However, it is no less important to establish a good relationship with him, so that he fully trusts us and feels motivated to face treatment.

Everything else is useless if we do not have a feeling with our patient, since this will have a negative impact on the rest of the variables: the person will stop attending therapy, will not commit to tasks between sessions, will not be motivated to achieve change and you will not trust what we propose or indicate as strategies.

Therefore, when we speak of therapeutic rapport we refer to the mutual understanding, the collaborative attitude and the empathy necessary for two people to be able to tackle a common problem and achieve the desired objectives. It is such a relevant therapeutic element that today future therapists are already taught in universities and there are even specialized courses aimed at training different professionals, especially healthcare professionals, who are going to have a deal with another person who has a problem that it is necessary to solve in collaboration.

Origins of rapport

The therapeutic alliance or rapport was developed throughout the 20th century. Already the well-known psychoanalyst Freud, in his 1912 work The Dynamics of Transference, raised the need for the analyst to have an interest and an understanding attitude towards his patient : the objective with this “strategy” was that the healthiest part of this established a positive relationship with the analyst.

Freud, in his early writings, defined the patient’s affection for the therapist as a beneficial and positive form of transference. Let us remember that for psychoanalysis, transference is the psychic function through which the client transfers his unconscious thoughts and emotions to another person, in this case the therapist.

This transference aspect promoted trust, acceptance and credibility in the therapist’s interpretations, as we have explained previously. However, later it was seen that it was not the transfer understood as such that generated that trust and climate of mutual collaboration between professional and client, since sometimes misunderstandings could arise in the relationship and this was not, in any case, positive .

Later, the concept of rapport or alliance was incorporated by most therapeutic schools, distancing itself from the transference reading provided by the psychoanalytic context. According to Rogers, father of the humanist school together with Abraham Maslow, special attention must be paid to the quality of the therapist-patient relationship. Rogers then proposed three fundamental characteristics that the therapist should possess: authenticity, unconditional acceptance of the patient and empathic understanding.

According to this author, the probability of therapeutic progress would depend less on the personality of the therapist and his attitudes than on the way in which they are experienced by the patient in the therapeutic relationship. For this interpretation to be positive, it is essential that they feel understood (that there is empathy) and accepted without conditions.

Later, Bordin, in the 70s, will describe the common characteristics that must exist in the therapeutic relationship in all schools. This author identified three components that make up rapport: agreement on tasks, positive bond, and agreement on objectives.

Techniques to generate good rapport

The two fundamental pillars on which rapport is currently based are trust and fluid communication. When we talk about fluid communication, we do not mean that it should be symmetrical, but rather that the important thing is that the therapist and the client understand each other at all levels: verbal and non-verbal.

Communication, in reality, must be asymmetrical, where the patient intervenes much more than the therapist. Some techniques that have been proven effective in establishing good rapport are:

Active listening

It is a simple technique a priori , but that on many occasions we find it difficult to carry out. It is about listening to what the patient has to tell us without interrupting him, with the predisposition not to make any value judgments, but showing through gestures and expressions that we are by his side, listening carefully, understanding what he wants to convey to us and empathizing with his emotions .

Warmth

For a good rapport to exist, it is extremely important that the therapist be warm with his client. A professional may know many techniques and harbor a great deal of knowledge and have a lot of experience. However, if you are not warm with your patient, all of this will not do much good.

As we have explained before, the person will not be able to trust their therapist, they will not be fully open to him and, therefore, much information will not come to light. In addition, the lack of confidence will have a direct impact on the degree of commitment of the patient with the therapy: a low confidence will increase the chances that the patient will not do the tasks that the therapist sends him out of consultation.

Empathy

It is obvious that putting ourselves in the shoes of the person in front of us is essential if we want to help him. It does not matter that our patient is a person who suffers from an affective disorder or is a criminal. If we are to deal with him, we must see the world from his eyes, even if we do not share his feelings or believe that his actions are right. Only by being empathetic will we build trust and be able to help the person.

Establish trust

As we have mentioned, for the future of therapy it is very positive that the patient feels confident and at ease when they attend therapy sessions. To build trust, in addition to everything we have just discussed, we must be credible and also appear so.

The person must perceive that we are professionals, that we are correctly trained and up-to-date and that, if in any aspect this is not the case, we will do our best to respond to their request as soon as possible, either by referring to another professional or by training in that aspect. concrete. In this way, the patient will trust that we will be able to help him.

Find common ground

This point refers to the need to focus attention on common interests. In this case, to move towards the therapeutic objective that was initially proposed by the client. It is important not to deviate from the subject and end up talking about common points, but that have nothing to do with our objective. If we do so, we would lose time in the session and in the end the relationship would cease to be asymmetric expert-client, something that is not recommended for therapy.

Coherence between verbal and non-verbal language

Let us try to be careful when communicating with our patient, since many times we say something that may be inconsistent with our expression or our gestures. The coherence between verbal and non-verbal language is fundamental in the therapeutic relationship since without it, it would not be possible to generate the climate of trust and collaboration that we have been talking about.

Therefore, it is necessary, as Rogers said, that we be authentic or genuine with our patient. Always taking care of the forms and maintaining warmth, acceptance and empathy, but without generating incongruities between our verbal and non-verbal language when expressing ourselves to our patient.

What to do when this good feeling does not occur?

Although all these techniques may seem like common sense, the truth is that they are not easy to put into practice when facing a patient in consultation: the therapist is also a human being, with his own values, attitudes, emotions, etc. ., and many times he has to leave them out of therapy for the benefit of its progress.

Even so, it may happen that we do not create a good relationship with the client and we should not be disappointed by it. As in informal relationships it can happen to us that we do not have a good feeling with someone, in the therapeutic relationship it can also happen to us, even if we do everything we can to prevent it from happening.

In this case, the most honest and sensible thing to do is to refer the patient to another professional with whom they can develop a better therapeutic alliance and can continue their personal growth. In this way, neither party is wasting time and we are on our way to what really interests us: the recovery of the patient.

Rapport is not empathy

It is important not to confuse the phenomenon of rapport with what we know as empathy. While the former is better understood as a process that occurs in a specific communicative dynamic, empathy is rather a set of psychological predispositions that occur in individuals, and that lead us to understand both how a person feels and thinks, even if we are not talking to her.

In practice, it is common for both notions to overlap (and of course, being an empathic person helps to establish rapport in a conversation), but it does not have to happen that way.

The importance of rapport in the therapeutic bond

To conclude, we emphasize the importance of rapport within psychotherapy, since it is one of the processes that promote the creation of an adequate therapeutic bond.

This notion refers to the set of expectations, and communication and support dynamics, which make it clear what the purpose of therapy is and the relationship between the patient and the professional.

It is about creating an appropriate conversational climate, which is not the same as that of conversations with friends, but not like the formal and impersonal dialogues typical of the business or corporate world. The psychologists make it clear that they empathize, but also that they are not there to give friend advice or to meet after the session. The raison d’être of these meetings has to do with offering the right psychological tools to a person who needs help.

Bibliographic references

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centered psychotherapy. Buenos Aires: Editorial Paidós.

Corbellá, S., Botella, L. (2003). The therapeutic alliance: history, research and evaluation. Publications service of the University of Murcia. ISSN: 0212-9728

Freud, A. (1936). The ego and the defense mechanisms. Wien: Int. Psychoanal. Verlag.