Blind Obedience: Milgram’s Experiment

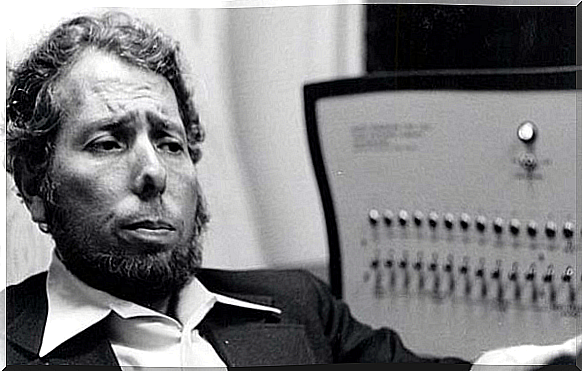

Why does a person obey? To what extent can a person follow an order that goes against his morals? These and other questions can perhaps be resolved through the Milgram experiment (1963) or at least, that was the intention of this psychologist.

We are facing one of the most famous experiments in the history of psychology, and also more important due to the revolution that its conclusions implied in the idea that we had until that moment of the human being. He especially gave us a very powerful explanation to understand why good people can sometimes be very cruel. Are you ready to learn about Milgram’s experiment?

Milgram’s experiment on blind obedience

Before we discuss obedience, we are going to talk about how the Milgram experiment was performed. First, Milgram ran an ad in the newspaper demanding participants for a psychological study in exchange for pay. When the subjects arrived at the Yale University laboratory, they were told that they were going to participate in research on learning.

In addition, their role in the study was explained to them: asking another subject about a list of words to assess their memory. Nevertheless…

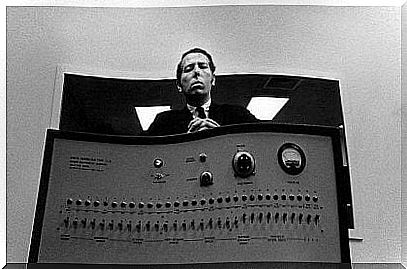

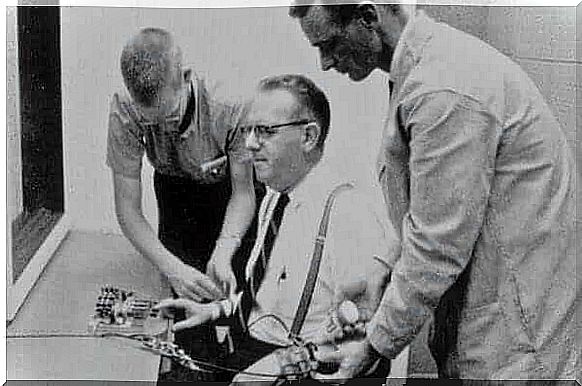

In reality, this situation was a sham that concealed the actual experiment. The subject thought that he was asking questions of another subject who was actually an accomplice of the investigator. The subject’s mission was to ask the accomplice questions about a list of words that he had previously memorized. If he was right, he would go on to the next word; in case of failure, our subject would have to give an electric shock to the investigator’s accomplice (in reality no shocks were applied, but the subject thought it was).

The subject was explained that the shock machine consisted of 30 intensity levels. For each mistake the infiltrator made, he had to increase the force of the discharge by one. Before starting the experiment, several minor shocks were already applied to the accomplice, which the accomplice already pretended to be annoying.

At the beginning of the experiment, the accomplice answers the subject’s questions correctly and without any problem. But as the experiment progresses it begins to fail and the subject has to apply the shocks to it. The accomplice’s performance was as follows: when intensity level 10 was reached, he had to begin to complain about the experiment and want to leave it, at experiment level 15 he would refuse to answer the questions and would show his opposition to it with determination. Upon reaching intensity level 20, he would feign a faint and thus an inability to answer the questions.

At all times the investigator urges the subject to continue the test ; even when the accomplice is supposedly passed out, regarding the lack of response as a mistake. So that the subject does not fall into the temptation to abandon the experiment, the researcher reminds the subject that he has promised to go to the end and that all responsibility for what happens is his, the researcher.

Now I ask you a question, how many people do you think reached the last level of intensity (a level of discharge in which many people would die)? And how many made it to the level where the accomplice faints? Well, let’s go with the results of these “obedient criminals.”

Results of the Milgram experiment

Before conducting the experiments, Milgram asked fellow psychiatrists to make a prediction of the results. The psychiatrists thought that most of the subjects would abandon the first complaint of the accomplice, about 4% would reach the level at which they simulated fainting, and that only some pathological case, one in a thousand, would reach the maximum (Milgram, 1974 ).

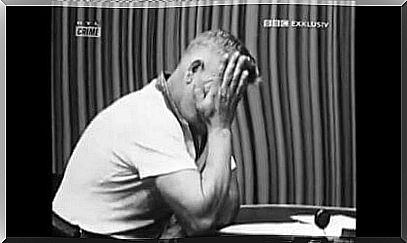

This prediction was totally wrong, the experiments showed unexpected results. Of the 40 subjects in the first experiment, 25 made it through. On the other hand, about 90% of the participants reached at least the level where the accomplice faints (Milgram, 1974). The participants obeyed the researcher in everything, although some of them showed high levels of stress and rejection, they continued to obey.

Milgram was told that the sample could be biased, but this study has been widely replicated with different samples and designs that we can consult in Milgram’s book (2016) and all of them have offered similar results. Even an experimenter in Munich found results that 85 percent of the subjects reached the maximum level of shocks (Milgram, 2005).

Shanab (1978) and Smith (1998) show us in their studies that the results are generalizable to any country with a Western culture. Even so, we must be careful when thinking that we are dealing with a universal social behavior : cross-cultural research does not show conclusive results.

Conclusions from Milgram’s experiment

The first question we ask ourselves after seeing these results is, why did people obey to those levels? In Milgram (2016) there are multiple transcripts of the conversations of the subjects with the researcher. In them we observed that the majority of subjects felt bad about their behavior, so it cannot be cruelty that moves them. The answer may lie in the “authority” of the researcher, in whom the subjects really relegate responsibility for what happens.

Through the variations of the Milgram experiment, a series of factors that affected obedience were removed:

- The role of the researcher: the presence of a researcher dressed in a gown, makes the subjects grant him an authority associated with his professionalism and therefore they are more obedient to the researcher’s requests.

- Perceived responsibility: this is the responsibility that the subject believes to have over their actions. When the researcher tells him that he is responsible for the experiment, the subject sees his responsibility diluted and it is easier for him to obey.

- The consciousness of a hierarchy: those subjects who had a strong feeling towards hierarchy were able to see themselves above the accomplice, and below the researcher; therefore they gave more importance to the orders of their “boss” than to the welfare of the accomplice.

- The feeling of commitment: the fact that the participants had committed to carry out the experiment made it impossible for them to oppose it to some extent.

- The rupture of empathy: when the situation forces the depersonalization of the accomplice, we see how the subjects lose their empathy towards him and it is easier for them to act with obedience.

These factors alone do not lead a person to blindly obey a person, but the sum of them creates a situation in which obedience becomes highly probable regardless of the consequences. Milgram’s experiment once again shows us an example of the strength of the situation that Zimbardo (2012) tells us about. If we are not aware of the strength of our context, it can push us to behave outside of our principles.

People obey blindly because the pressure of the aforementioned factors outweighs the pressure that personal conscience can exert to get out of that situation. This helps us to explain many historical events, such as the great support for the fascist dictatorships of the last century or more concrete events, such as the behavior and explanations of the doctors who helped the extermination of the Jews during World War II in the Nuremberg trials. .

The sense of obedience

Whenever we see behaviors that go beyond our expectations, it is interesting to ask what causes them. Psychology gives us a very interesting explanation of obedience. It starts from the assumption that the decision made by a competent authority with the intention of favoring the group has more adaptive consequences for the group than if the decision had been the product of a discussion of the whole group.

Imagine a society under the command of an authority that is not questioned compared to a society where any authority is put on trial. By not having control mechanisms, logically the first will be much faster than the second executing decisions: a very important variable that can determine victory or defeat in a conflict situation. This is also closely related to Tajfel’s (1974) theory of social identity, for more information here.

Now, what can we do in the face of blind obedience? Authority and hierarchy may be adaptive in certain contexts, but that does not legitimize blind obedience to an immoral authority. Here we are faced with a problem, if we achieve a society in which any authority is questioned, we will have a healthy and just community, but that will fall before other societies with which it comes into conflict due to its slowness in making decisions.

At the individual level, if we want to avoid falling into blind obedience, it is important to keep in mind that any of us can fall under the pressures of the situation. For this reason, the best defense we have against them is to be aware of how context factors affect us; so when they are going to overcome us, we can try to regain control and not delegate, no matter how great the temptation, a responsibility that corresponds to us.

Experiments like this help us a lot to reflect on the human being. They allow us to see that dogmas such as that the human being is good or bad, are far from explaining our reality. It is necessary to shed light on the complexity of human behavior in order to understand the reasons for it. Knowing this will help us understand our history and not repeat certain actions.

References

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 67, 371-378.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York: Harper and Row

Milgram, S. (2005). The dangers of obedience. POLIS, Latin American Magazine.

Milgram, S., Goitia, J. de, & Bruner, J. (2016). Obedience to authority: the Milgram experiment. Captain Swing.

Shanab, ME, & Yahya, KA (1978). A cross-cultural study of obedience. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society .

Smith, PB, & Bond, MH (1998). Social psychology across cultures (2nd Edition) . Prentice Hall.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behavior. Social Science Information, 13 , 65-93.

Zimbardo, PG (2012). The Lucifer effect: the reason for the evil.